Comp Team Expense Ratio (Part 2)

The second of a 3-part series exploring the economics of compensation management

In my most recent newsletter post, I compared compensation teams to Wall Street firms managing billions in assets, including their annual comp spend (“portfolio”) and annual decision value (“turnover”).

A key insight from this analysis: the turnover of compensation investment is high and requires active management, like a mutual fund.

A mutual fund has more expensive management fees, or expense ratio, because it trades more actively.

So you might expect the comp team to be sized similarly to a mutual fund as a percentage of its portfolio.

How big should your comp team be?

That’s exactly what we dig into in this post, the second in a three-part series.

And no, we’re not using the usual headcount math; this time, we’re using money.

Comp teams are like mutual funds

We estimated that a 10,000 person tech company manages a $2 billion compensation portfolio with ~$950 million in annual turnover, or 47.5%.

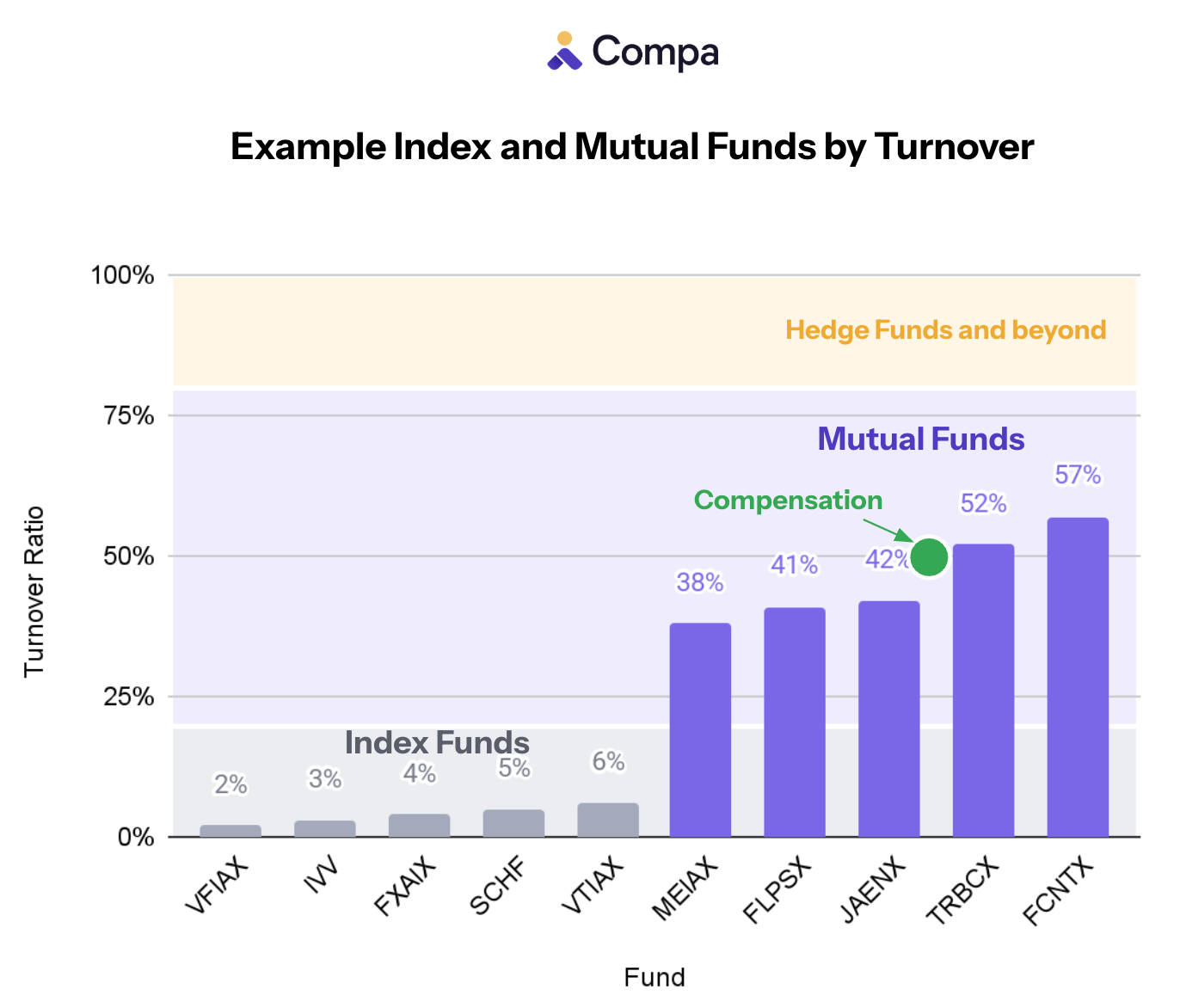

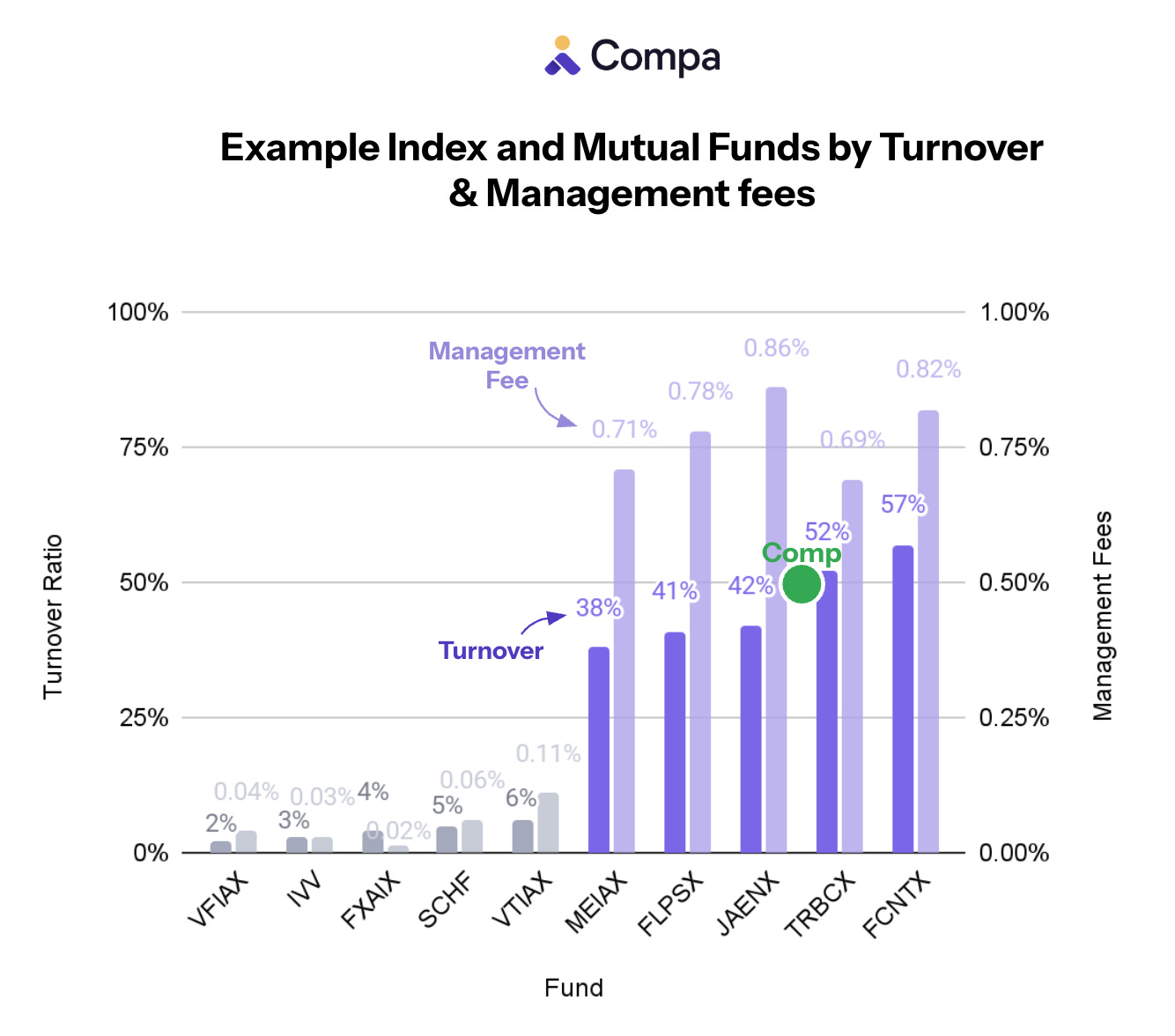

Turnover is a useful metric to understand how actively the investment team manages a portfolio, i.e., how expensive is it to manage the money.

Index funds are passively managed and turnover, or trade, very little each year, 2-6%.

Mutual funds are actively managed and turnover a much larger percentage of the fund each year, 40-60% — similar to compensation teams.

Turnover correlates with management fees, or expense ratio, expressed as a percentage of investments managed:

Index funds charge very little, ~0.02%-0.10% expense ratios, whereas mutual funds charge ten times more, ~0.70%-0.90%.

And this makes sense: the more activity — buying and selling — the more people and cost needed to manage those transactions.

Comp very closely resembles a mutual fund profile in turnover.

What about management fees?

That is, do we size our compensation teams similarly to a mutual fund, 0.70%-0.90% expense ratio?

Sizing your comp team, “expense ratio”

Comp team “expense ratio” consists of headcount and discretionary spend. Let’s size it.

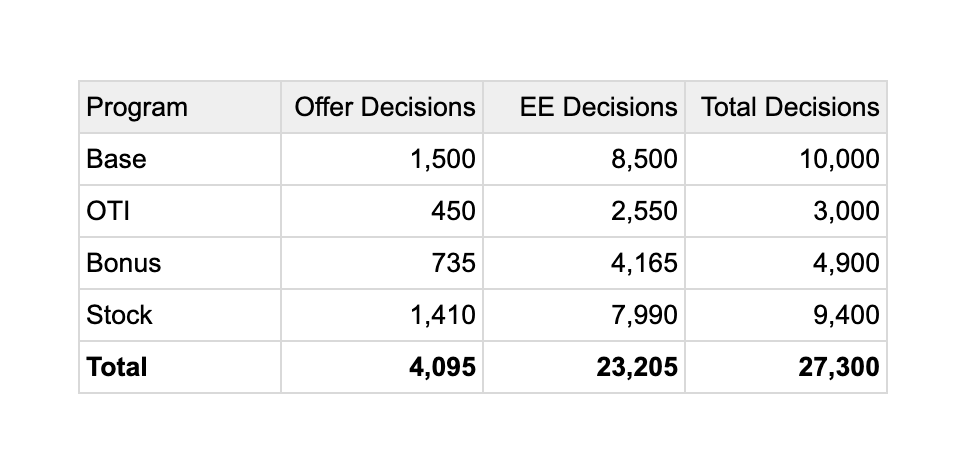

Our 10,000 person tech company with a $2 billion compensation portfolio and 47.5% turnover has the following 10-person comp team:

VP Total Rewards

Exec Comp Director

4 Comp Partners (R&D, GTM, G&A, International)

Comp Programs Manager

3 pooled Analysts

Using the market 50th percentile total direct comp using data from Compa, this team costs ~$3.2 million.

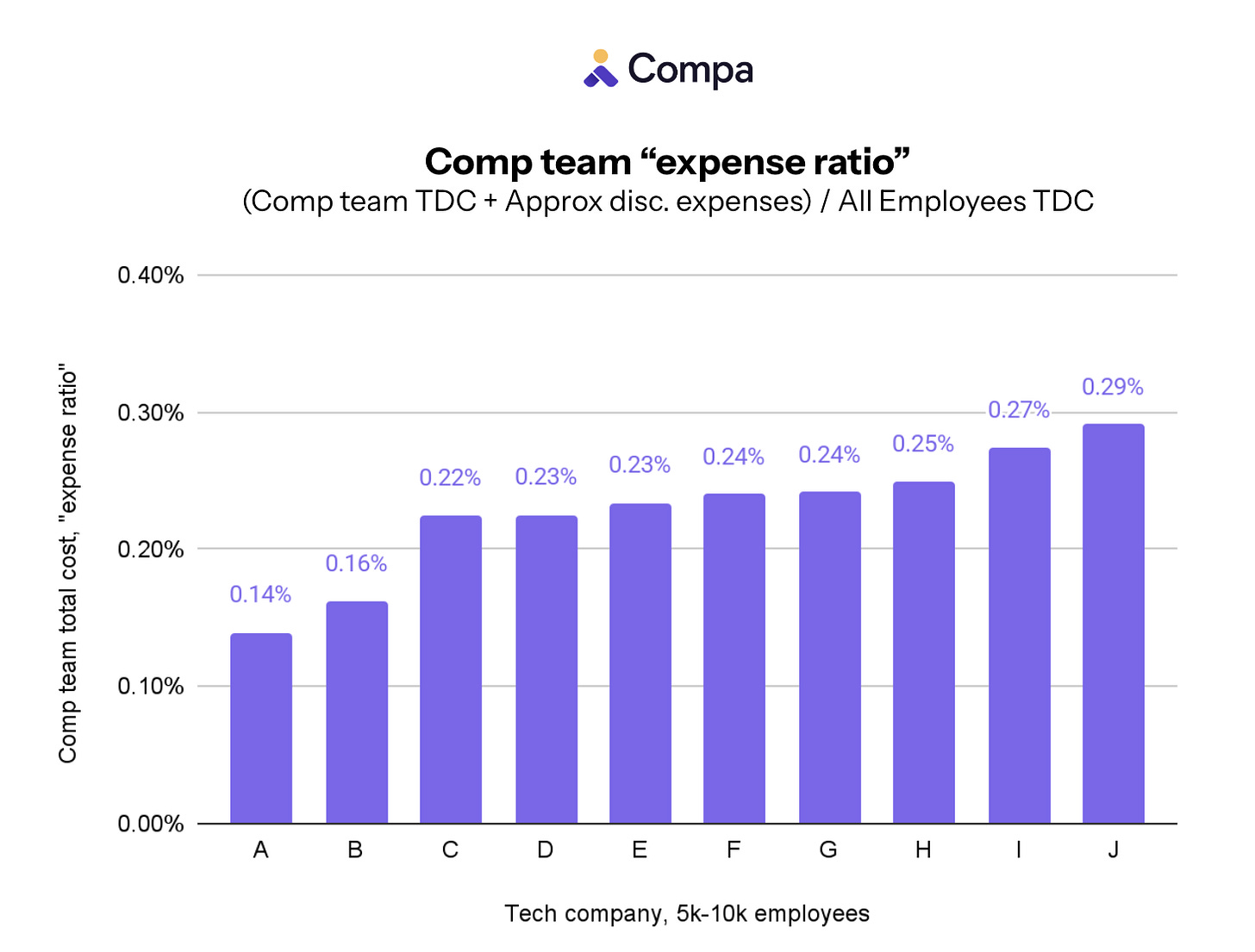

Adding $500k discretionary budget for market data, software, and other expenses like consulting projects and team travel, the total cost is $3.7 million, or 0.19% of the $2 billion compensation portfolio.

This is a hypothetical model for our tech company. Looking at an example set of 10 similar tech companies in Compa ranging 5,000-10,000 employees, we see a similar estimate, 0.14%-0.29% expense ratio.

But with the mutual fund comparison, we expected expenses closer to 0.70%-0.90%, or $14-$18 million each year. Instead we’re seeing a third of that.

Why are we spending so much less than expected?

…And should your comp team be three times bigger?

Comp triage

I think the answer is coverage.

Realistically, most teams actively manage a small (and noisy) fraction of all pay decisions across all comp programs — exceptions and outliers and exec comp — and leave the rest to discretion by recruiters and managers within a broad set of policies.

If we estimate comp teams actively manage only 20% of all pay decisions annually, with the balance passively managed via decision-makers out in the business, we can weight the predicted “management fees” to find the mutual fund comparison is very close to our 0.19% estimate.

20% active management: 0.80% mutual fund fees

80% passive management: 0.05% index fund fees

(20% * 0.80%) + (80% * 0.05%) = 0.20% comp feesCost per pay decision

So why not have a much bigger comp team?

Like a mutual fund aims for outsized returns with more active management, should comp do the same?

The underlying problem is that, unlike mutual funds, our compensation portfolios are fragmented into thousands of decisions, and humans are too expensive to manage all of them.

Looking back at our comp programs breakdown from my first post, we can add up the number of decisions involved for each program’s turnover based on the employee population.

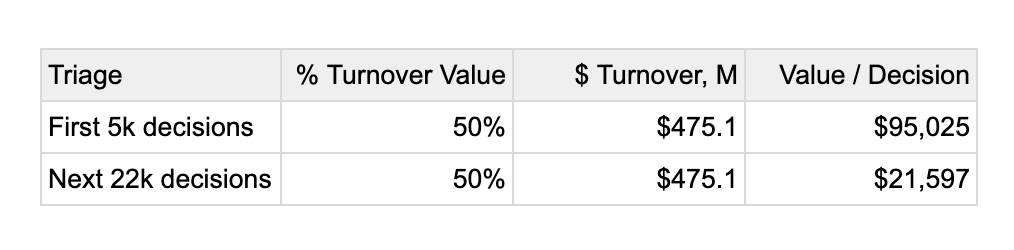

Comp teams will triage these 27,000 decisions on a power curve, actively managing the most valuable decisions and passively managing the rest. If the top 20% of decisions are worth 50% of all turnover, we can calculate the per decision cost and value to reveal our unit economics problem.

(Buckle in for a some economics math, it’s worth it.)

Starting with the decision value: our top 5,000 decisions are worth way more than the remaining 22,000:

What about the per-decision cost?

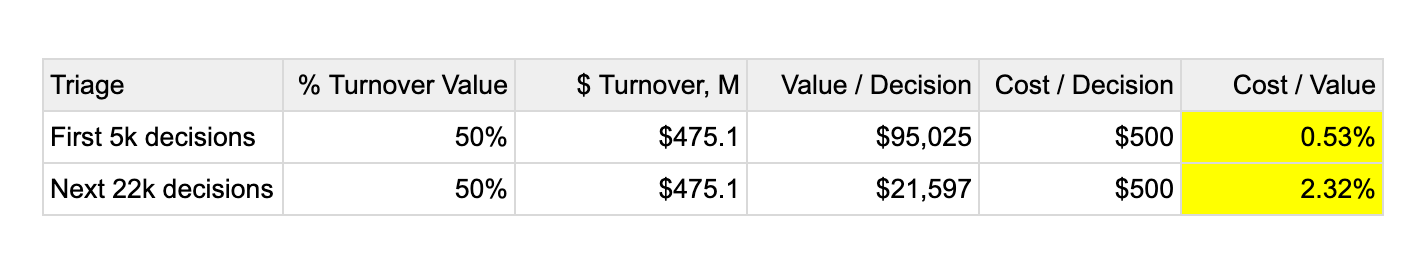

If our 10-person comp team is actively managing only the top 5,000 pay decisions, then each person has capacity for 500 pay decisions. Assuming a TDC cost of $250k/comp person, each actively-managed comp decision costs $500.

Now the problem is emerging — comp people only have so much time in the day, and they cost a lot. The unit economics look good for the most expensive decisions, but look terrible for the rest.

The “management fees” for the most expensive comp decisions are rational, 0.53%, similar to a mutual fund.

But for everything else, it’s cost-prohibitive.

Actively managing the remaining 22,000 decisions would cost 2.32%, off the charts from our mutual fund comparison.

Your comp team size is a function of the value of your portfolio and the quantity and value spread of its underlying decisions.

The $1 billion dilemma

Our 10,000-person tech company actively manages only half its portfolio value, leaving $1 billion to passive management — discretion within broad ranges, managers and recruiters with little training and context, high-level philosophies.

Your instincts might say, “let’s add one more comp person, if they optimized even 1% of that $1 billion, they could create $10 million in value.”

But herein lies the dilemma.

There are too many thousands of decisions to wrangle — one more person tackling 500 decisions worth $22k each can optimize only $11 million in value. You’d need 40 more comp people costing $10 million to get to every remaining decision, erasing all of your ROI.

AI breaks the impasse

The bottleneck is human cost and capacity to manage thousands more decisions. So we keep our comp teams small and only manage the hardest, most valuable decisions.

But AI agents introduce something new: the potential to manage thousands of decisions simultaneously at a fraction of the cost.

With AI, a comp team can radically expand its reach to every pay decision in the company with rational unit costs, unlocking tens of millions in ROI for the first time.

This, in my view, makes AI transformation inevitable.

The economics of AI will change compensation management forever.

And this will be the topic of my next and final post in this series.

Peer Group is a newsletter for comp leaders navigating competitive talent markets and AI transformation! If you want to share my newsletter, you can forward this email to your colleagues and fellow comp leaders.

Want more polls and insights about the latest thinking in comp?

Subscribe by hitting the button below.

This post is a wake-up call. We’re managing billions in pay decisions, yet still sizing comp teams like it’s 2005. Your comparison to mutual funds nails it, active management drives results, but comes at a cost. What changes everything is AI. It’s not about adding more people. It’s about scaling smart, reaching every decision, and unlocking value where humans simply can’t. You’re not just forecasting the future, you’re mapping out the next comp playbook. Can’t wait for Part 3.

Love the analysis. AI is one solution. Good bands and manager/recruiter training and resources would be another way. A Comp person who was solid at comp but strong at communication and training or recruiters who understand the impact on those “passive” funds by creating more active managers. We saw a significant improvement in equity offer metrics after spending just one hour explaining how burn works to our recruiters so they understood how every extra share of equity (previously thought of as “free”) diluted the value of everyone’s shares—including their own.